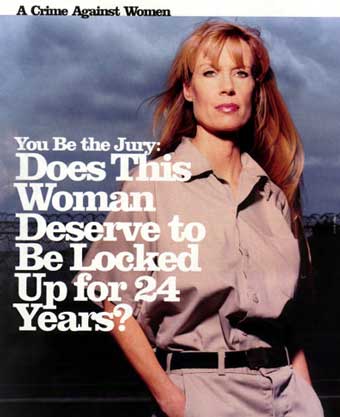

You be the Jury:

Does This Woman Deserve To Be Locked Up for 24 Years?

AMY POFAHL’S DRUG-KINGPIN HUSBAND CUT A DEAL THAT DUMPED HER IN PRISON FOR A QUARTER CENTURY—AND FREED HIM AFTER FOUR YEARS. GLAMOUR INVESTIGATES HOW SHE AND THOUSANDS OF OTHER WOMEN GUILTY OF RELATIVELY MINOR CRIMES END UP DOING MORE TIME THAN MEN DUE TO A CONTROVERSIAL FEDERAL LAW.

A harsh law punishes women unjustly and lets drug lords off easy.

BY DAVID FRANCE • From GLAMOUR magazine, June 1999. p. 224

THERE IS AN INTENSE CALIFORNIA SUN on the morning I pass the two rows of gleaming razor wire, the metal-detector arch, the armed guards and two vault-like doors before arriving at a brick patio inside FCI Dublin, a low-security women’s federal correctional institution outside of Oakland. Amy Pofahl stands on the other side of the terrace, her feet next to a patch of pansies with a sign stuck in it that reads, “No Inmates Allowed Beyond This Point.” She was once an exceptional beauty and a very wealthy woman, and even in her regulation beige work shirt and slacks, she is still striking—graceful and leggy, with silken hair that drapes her shoulders in countless shades of gold. With her top two buttons undone, revealing a glimpse of her simple white T-shirt, she looks like she is ready to leave on a safari, which couldn’t be further from the truth. Amy last saw freedom eight years ago, when she was a 30-year-old nightclub promoter in Los Angeles. Now, the toll of her long incarceration shows on her face, particularly on her lazy eyelids, which are as creased as crackled pottery.

As the warden’s assistant and I approach Amy, he points to her neckline and commands, “Button your shirt.” She complies with a slow hand. Later, she whispers to me, “Being in here is very much like that. Everything starts to focus on these little things like how to wear your shirt. And whenever you’re trying to focus on something that’s maybe going to get you free ….” Then her eyes leave mine, and she flutters the long fingers of her right hand in the air, pawing for emotional control.

Amy Pofahl broke the law, but she is not a hardened criminal. Like thousands of women in prison today, she is a once-productive member of society who made a series of bad decisions, all for a man she loved. Unbeknownst to Amy, for most of the time she was married to him, Charles “Sandy” Pofahl—a Stanford University Law School graduate and wealthy Dallas businessman with whom she exchanged rings when she was 25 and he was 44—was the mastermind of a secret and illegal international syndicate that made and distributed the drug MDMA, or Ecstasy. Sandy revealed his involvement to Amy after his arrest on February 16, 1989, three years into their marriage. But then he begged her to handle some financial matters that she felt might be shady while he awaited trial. Out of love, she agreed. “I have the kind of personality that was just right for him to rely on,” she explains. “It’s a flaw in my character. I’ll jump off end do things and ask questions later.”

It’s bad enough that Amy became criminally embroiled in an operation her husband ran and had kept her in the dark about. What’s worse is that Sandy Pofahl, an ecstasy ‘kingpin’ who directed nearly two dozen accomplices to smuggle millions of pills into America, served just four years in prison. Amy Pofahl, his blindly loyal wife who did nothing even remotely like that, got 24 years with no chance of parole.

Women Bear the Burden

It is a peculiar facet of the federal sentencing guidelines that women, many of them young, who are convicted in drug rings often draw much longer sentences than men. Almost always, their connection to the drug ring is as a gofer, delivery person or patsy for the men they love. As a result, there are more women in prison today than at any time in the nation’s history. The latest data, from July 1998, shows that 146,507 women are serving time in federal, state and local facilities, up from 63,015 a decade earlier. Nearly half of that increase is drug related, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, part of the US Department of Justice. This is certainly the most unanticipated and least logical consequence of the war on drugs.

At the height of crack cocaine’s terrible march through American cities in the mid-eighties, entire neighborhoods succumbed to crime of such violence and scope that it seemed as if the fabric of American civilization was in danger of unraveling. Congress responded by passing The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, which removed sentencing discretion from federal judges and established a schedule of mandatory-minimum prison sentences in drug cases, based solely on the type and quantity of drug involved. The only way defendants can earn a “downward departure,” or reduced sentence, is to give “substantial assistance” in the prosecution of other drug dealers.

The Anti-Drug Abuse Act has drawn sharp criticism, largely because it penalizes low-level participants and drug users as harshly or—as in Amy Pofahl’s case—more harshly than people guilty of running major drug operations. The mandatory-minimum sentences established by the Act have been slammed by the American Bar Association, the US Sentencing Commission, Supreme Court Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist and an astonishing 86 percent of federal judges. Barry R. McCaffrey, the four-star general who heads the Office of National Drug Control Policy, has called mandatory minimums “bad drug policy and bad law,” and decried the fact that they dominate the drug-war budget: Some $35 billion a year are spent on incarcerating drug convicts, many of whom McCaffrey considers mere foot soldiers for big-time dealers.

Even the congressional staffer who wrote the law, Eric Sterling (now president of The Criminal Justice Policy Foundation, a Washington, DC, think tank), works tirelessly today to undo his legacy. “The statute has been profoundly misused,” he says. “The price has been a tremendous injustice and a tremendous tragedy for the [less culpable] individuals, their children, their parents, their siblings and their spouses.”

The Price of Loyalty

The primary reason women have been hit hard by the Anti-Drug Abuse Act is that the original statute was amended in 1988 to add “conspiracy” to the list of offenses covered. Technically, a conspirator knows about criminal activity and has agreed to participate. But federal prosecutors have been able to convict people they believe simply should have known about the ongoing crimes, says Marc Mauer, an authority on crime trends at The Sentencing Project, a Washington, DC-based nonprofit group. Frequently, that means the wife or girlfriend of a dealer ends up behind bars, says Monica Pratt, of the national organization Families Against Mandatory Minimums. “Almost half of the women in prison today under mandatory-minimum sentences have been convicted of conspiracy. Taking messages for a drug dealer, driving him to a bank to deposit his money—that can make you just as liable as the dealer,” she says.

In part because of the crackdown on “conspirators,” the female prison population is growing faster on average than the male population—7 percent versus just 4.5 percent a year since 1990. Also, of the 8,207 women currently serving time in federal prison, 60 per cent have been convicted of drug charges.Casualties of the drug war include women such as Kemba Smith, 27, a former Virginia debutante (see below). She ended up facing the same stiff penalties as some of the principal dealers in her college boyfriend’s drug ring, even though evidence at her sentencing showed that he beat her, and that out of fear, she sometimes participated in illegal activities for him. She was convicted not of specific crimes related to those few incidents, but for many offenses the drug ring had collectively committed. At the age of 24, she was sentenced to 24-and-a-half years without parole. By comparison, the average maximum sentences that state courts handed down for rape and robbery in 1996 were 11-and-a-half and eight-and-a-half years, respectively, while the average minimum state sentence actually served for rape was only six years, and for robbery, five.Why are women like Pofahl and Smith receiving such long sentences? Because when wives and girlfriends are caught in the net, especially if they genuinely know little about the drug operation, they seldom have the kind of information to trade for a “downward departure.” So the law that was meant to crush drug-world master minds actually rewards them with shortened sentences, while their less culpable sweethearts are vigorously punished.Even if women have information to trade for reduced sentences, however, they often decline to cooperate out of loyalty. In 1989, Serena Nunn, now 29, refused to inform against her boyfriend, Ralph Nunn (no relation), a member of a Minneapolis drug ring (see below). “I would not hurt someone else to save myself,” Serena said. “I’m just not made like that.” For her minimal role, she got a 16-year sentence. Had she informed on her boyfriend, she might have received as few as eight months. Instead, Marvin McCaleb, a senior partner in the drug ring, informed on Ralph Nunn, who received a 25-year sentence. McCaleb, who had previously been convicted and served time for manslaughter, major drug dealing and rape, got seven years—less than half Serena’s sentence.In response to such cases, Rep. Maxine Waters (D Calif.), a long time advocate of Kemba Smith, introduced a bill in Congress last month to eliminate mandatory minimums. “If you had to define injustice at the turn of the century,” says Eric Sterling, “these cases are Exhibit A: the girlfriends of king pins who get sentences that are two and three and four times longer than the guys who head it all up.”

Sandy and Amy Pofahl in 1988: “I thought he was the best thing in the world.”

The End Of Innocence

Amy Pofahl was once a shy girl from little Charleston, Arkansas, where her mother was the news paper editor and her father served a term as mayor. She preferred her 4-H Club activities to dating, and only begrudgingly attended her junior and senior proms. That changed when. after a year of college, she moved to Dallas, a 19-year-old with dreams of becoming a model. At a party in March 1985, she struck up a conversation with another guest, Sandy Pofahl. He was 19 years older, a balding businessman who reminded her of Gene Hackman. But he had tremendous magnetism. “I was feeling emotions I never felt before. I thought he was the greatest thing in the whole world,” Amy says.

A few days later, they met for dinner at Cafe Pacific, one of Dallas’ finest restaurants, and he handed her an Ecstasy tablet Although it was sold legally as a diet aid at the time, Ecstasy is a psychedelic drug, like LSD, that fosters feelings of intimacy and love. Popularized in the eighties by San Francisco marriage therapists, it was sold in night clubs and herb shops until it was outlawed in October 1986. Using the drug tightened the bond between Amy and Sandy. They were engaged within eight days and married before the year was out. “She called and said, ‘You’re just going to love him. He’s my soul mate!’ “recalls Amy’s mother, Nancy Ralston. “When we met him and realized he was not a big, handsome man, I thought, It must be love!”He bought Amy a blue Mercedes and made her sales vice president of one of his businesses, Commonwealth Bancorp, specializing in home improvement loans. She earned $4,000 a month plus commission.

Sandy Pofahl was one of the frenetic entrepreneurial high-fliers who distinguished Texas in the eighties. He had graduated from Stanford before storming the business community in Dallas. By the time he met Amy, he owned or co-owned businesses including a mortgage lending company, an oil and gas business, a computer software company, a computer hardware company, a real estate brokerage and a half-dozen other concerns. He and Amy lived in a sprawling home in Highland Park, Dallas’ most exclusive suburb, and traveled the world. “These were people who in Texas we call highfalutin,” says an attorney familiar with the case. And though Amy says they never tried any harder drugs, the Pofahls continued taking Ecstasy at a time when it was exceedingly popular and entirely legal.

Sandy entered the Ecstasy business in early 1985, several months before he and Amy were married. Together with Morris Key, Ph.D., a Dallas chemist, Sandy established Ecstasy International Export and Import Organization (EIEIO) and sank nearly a million dollars into start-up costs. Their main plant was in Guatemala, and they employed a network of above-board distributors. In October of 1986, however, Ecstasy was added to the Drug Enforcement Agency’s (DEA) list of illegal drugs. Despite this, Amy says neither she nor Sandy stopped taking it occasionally. Still, Amy has consistently said she was unaware that Sandy and Key continued with their business, and her protestations seem credible: “Sandy went from one business meeting to another, all day long. It was impossible to keep up with his affairs,” she says. “It was like being Jane Fonda married to Ted Turner.” EIEIO eventually established production contacts in Germany, where it was easier to get the necessary materials, smuggling millions of pills into America over the next two years, according to federal authorities. “I knew he had access to Ecstasy, and he had said he could get as much as he wanted, but I didn’t think he was manufacturing it,” Amy says.

Meanwhile, their marriage was crumbling. Friends say Sandy had a drinking problem, which fueled grossly inappropriate behavior “I couldn’t stand him,” remembers Kathy Johnston, a friend from North Dallas. “It seemed like anytime you’d even get close to him, he’d try to touch you. I found him obnoxious. But Amy was in love with the creep.”In love or not, by January 1988 Amy had had enough of Sandy’s drunken flirtations. She moved to Los Angeles, leaving Sandy behind. She thrived there, and was soon throwing such glamorous parties in her home that the owners of Tramp, the exclusive Hollywood supper dub that Jackie Collins opened, hired her as their promoter. She earned $80,000 a year and hosted celebrities from Jean-Claude Van Damme to Eddie Murphy. “She knew absolutely everybody,” says a soap opera star who befriended her then and still keeps in touch. “I liked her independence; I loved that she was out there doing this on her own.”

But Sandy’s spell was not easily broken. He wrote letters with lovelorn salutations like “Dear Better Than Bestest” and visited her often. He even signed the lease on a $42,000 a-year house in the Hollywood Hills to be close. His campaign worked. “If Sandy could get within a 20-foot radius of me, he could just completely melt my heart,” she says.

Amy agreed to move into the rented home with him, but before she did, Sandy left on a mysterious business trip to Germany. A week later, on February 16, 1989, he was taken into custody by German federal agents. Two days later, his partner, the chemist Key, was arrested in New York City and extradited to Germany for trial. When word of the charges reached Amy, she was blown away—not by her husband’s criminal activity, but about the danger the man she adored was now facing. “I was going to do whatever I needed to do to help him. I didn’t care what he’d done,” she says.

Amy (right) and a friend in 1987, four years before Amy’s arrest.

“How would you like to be told to plead guilty to something you didn’t do?”

Kept in the Dark

Other members of the EIEIO drug ring were rounded up by the DEA, but many didn’t even know Amy Pofahl’s name. When agents from the U.S. attorney’s office interviewed her husband and Key in their German prison, both said that Amy—like all wives and girlfriends—was told nothing about the Ecstasy operation. Daniel Bernard, one of Sandy’s main U.S. distributors, would later write in an affidavit: “I never believed Amy to be knowledgeable as to the particulars. Quite the contrary. I personally observed numerous attempts made by Mr. Pofahl to shield Amy from his MDMA enterprise, and I aided his endeavor to hinder Amy from knowing about the operation.”But after Sandy’s arrest, Amy, who had moved into the rented house alone, became very involved. Sandy anticipated (wrongly, as it turned out) that he would be offered a chance to post bail. So he sent his wife a series of coded faxes imploring her to help recover his hidden drug profits and cryptically telling her where to find them. Amy wanted him out on bail badly enough to take the risk. “What kept going through my mind is that incarceration is worse than losing someone to death,” she says, fighting back tears. “You know that they’re unhappy, and you know there’s nothing you can really do.” Besides, she convinced herself that as his wife trying to help him ferret out cash, she would not be breaking any laws. The crime, she reasoned in her distress, remained his responsibility.In any case, by the end of the summer of 1989, she had collected more than $780,000 from the various places Sandy had stashed it, and had hidden the cash in attics and shoe boxes in Dallas and Los Angeles. But then she found out that Sandy would not be offered bail, and she was stuck with the dirty cash. “The money,” she says, “became this enormous albatross.”Having secretly monitored Amy’s actions, federal authorities descended on her one afternoon in September 1989. She arrived home to find agents rifling through her things. The list of seized items included six Ecstasy tablets found in one of Sandy’s coats and $7,000 in cash earmarked for rent on the house, which, of course, was leased in Sandy’s name. She recalls an agent saying, “You’re in deep, sister.”One who questioned her was Charlie Strauss, an assistant U.S. attorney from Waco, Texas. “She was told we were just interested in what knowledge she had, and we wouldn’t use it against her husband,” Strauss remembers. “Had she come to the table at that time — cooperated, been truthful, honest and candid — I would say there’s a probability she wouldn’t have been prosecuted.” Amy says she didn’t believe them. She says they wanted her to visit Sandy to collect incriminating information. (Strauss could not confirm this.) Out of love and respect for her marriage, she says, she refused.Sandy, it turned out, had fewer compunctions. In exchange for a promise of leniency, he soon told German and American authorities everything he knew about the operation, from the street dealers to the smugglers. He also offered information about his wife’s handling of his money. Rewarding him for the assistance, German authorities handed him a six-year sentence.

Sold Out and Set Up

In a vague note he sent to Amy, Sandy told her he’d come dean about everything, and encouraged her to cooperate, too. She was livid that she’d covered for him for no reason, but she did nothing. She did not know how much trouble she was in. “Once they had him and he had told them everything, I was sure they didn’t want me anymore.” On the contrary, they were building a major case against her based upon her husband’s sworn statements. Federal authorities seized her car and plundered her bank accounts, asserting that the money was ill-gotten. They even confiscated her wedding ring. Agents asked Tramp regulars if they’d ever seen her dealing drugs. Nobody had, but she lost her job anyway.

For about 19 months, federal agents kept on the pressure, and Amy nearly broke down. Her bank account empty and her credit cards canceled by the bank, she started spending the money she had collected at Sandy’s behest.Early in 1990, she says, she asked her attorney to tell the authorities that she would direct them to the remaining cash if they in return would stop investigating her. Strauss says the message never got to him. “Either she’s lying, or she misunderstood, or somebody’s given her some misinformation,” he says. “But those overtures never came to us.”

Fearing that her arrest was imminent but still convinced of her own innocence, Amy fled. She recognizes in retrospect that this was a mistake, but at the time, she says, sitting around and waiting to be indicted was just too stressful. “Every time I tried to do something to make it better, I got in deeper. I never made a right decision in this whole thing.” On the lam for about three months, she found her way to Florida. But the isolation from friends and family soon caused her to despair, so she headed back to Marina Del Rey resolved to fight. Agents from the DEA arrested her there on March 27, 1991, and charged her with conspiracy to import and distribute MDMA and money laundering. She was shipped to Waco, Texas, to await trial.

Her court-appointed attorney, John Hurley, urged her to plead guilty in hopes of a reduced sentence. She refused. “How would you like to be told you need to plead guilty to something you feel you’re absolutely positive you didn’t do?” she asks rhetorically.

At trial, there was no evidence that she ever had direct contacts with Ecstasy manufacturers or importers or personally sold the drug after it became illegal. But her efforts to retrieve her husband’s money were well documented. Sandy, still in his German jail cell, was not called to testify by prosecutors. He wrote to Hurley, pleading with the lawyer to be called as a witness on Amy’s behalf. For some reason, Hurley did not take him up on the offer (Hurley refused to comment for this article.) A jury of eight women and four men found Amy guilty on all counts. According to the mandatory-minimum sentencing laws, her involvement in the “conspiracy” made her just as culpable as if she had built the organization herself.

Unable to weigh her relative conduct, a federal judge was forced to hand Amy a 24 year sentence. If she had been found guilty of money laundering alone — the only charge alleging her direct involvement — she would probably have received a sentence of just five years.

Today, even the prosecutor, Charlie Strauss, seems chagrined that Amy received such a harsh punishment. “I don’t think Amy was the linchpin here,” he says. “If she were not married to Sandy, she would not have done this. She got involved through her association with him.”

Life Behind Bars

At FCI Dublin, Amy Pofahl shares a closet size room with another prisoner, their beds just a foot apart opposite a sink and an open toilet. Amy has been an exemplary prisoner with only two minor reprimands, the more serious for feeding sardines to the cats that dart between the squat prison buildings.

Amy has had plenty of time to reconsider her actions. She now concedes that the government’s money-laundering case against her, charging that she removed and spent money from Sandy’s vaults, is valid. “From my soul, I knew that the money was illicit, and I did spend it, and if that constitutes money laundering, absolutely. Absolutely, I regret it,” says Amy.”I’ve thought about the whole thing a million times,” she continues. “It’s going to sound phony, but it’s really true — I just feel now that my loyalties were displaced.”

Sandy Pofahl, meanwhile, served only four years and three months in a German prison, and although the authorities there expected him to serve another 17-and-a half years behind bars in America, the Justice Department elected not to require more time because he had cooperated with U.S. authorities. He left prison in 1993 and spent two years in the Netherlands, while his attorneys confirmed that he would not be prosecuted in America. He returned in 1995 and has since rebuilt his legitimate business empire in Dallas. The first time Amy heard anything from him after her conviction was two years ago, when she was served with divorce papers. After 12 years of marriage, Sandy cited irreconcilable differences.In a guarded, hour-long phone interview with Glamour, Sandy Pofahl rejected any responsibility for Amy’s incarceration. He put the onus on her, despite his well-documented pleas for Amy to retrieve his ill-gotten cash. (Sandy’s faxes asking for Amy’s help were used as evidence against both of them.) “She had a need to help,” he says, explaining Amy’s attempts to free him from a German prison. “I went over to Germany, and I truly don’t know what happened when I was over there.” Asked why he chose a divorce filing as his first contact with her after his release, he said: “I was considering getting married … so I needed to divorce her. It was important for both of us to get our lives going.”

Sandy finally visited Amy a year and a half ago when he was in the San Francisco Bay area for a school reunion at Stanford. She agreed to see him because she had questions: Why had he told authorities about her role gathering up his funds? Why had he implicated her instead of protecting her, as she had protected him? They sat beneath a craggy pine tree on a terrace behind the FCI Dublin visitors center. He was nervous. She was suspicious. When he tried to kiss her on the side of the head, she pulled away. “It was heartless,” Amy recalls. “I said, ‘Sandy you could clarify a few things for me!’ He was dead set against it and wanted to talk about surface stuff. I said, ‘In case you haven’t noticed, there’s razor wire around this little place where I live. Stop acting like we’re sitting at a sidewalk cafe in Los Angeles, because I would really like to talk to you about some of the things that happened.”‘

Sandy showed no sign of guilt or remorse, Amy says. Regardless, she harbors no anger—at her ex-husband, the prosecutor or anybody else. But it is harder for her mother, Nancy Ralston, to let go: “I pray that I will not be bitter. But it’s difficult, it’s very difficult.”

Endless Sentence

Only one other target of the EIEIO prosecution besides Amy is still behind bars. Amy herself has filed two appeals citing incompetent legal counsel and plans to seek other remedies, but in truth, her chances of early release are slim. If she serves the full term of her sentence as expected, she’ll be 55 years old when she gets out in 2015. Even if she were set free tomorrow, Amy would have already spent twice as many years behind bars as her husband, a fact she knows will never be changed.

“I have regrets, of course I have regrets,” Amy tells me on the last day of our prison visit, her voice heavy with emotion. “I’m getting to the period in my life where I just feel like I’m losing my youth and the opportunity to have children and to set up some kind of a future. I lost the prime years of my life. Nothing’s worth losing that, nothing.”More about Amy PofahlThe November Coalition is a national support group for Drug War POWs, their friends and families.

| BURNED by Bad Men and Now Behind Bars: These women earned major prison time for minor offenses. By Erin E. Bried and Joshua Tager |

. |